Dangerous Book Club: Coming Apart, The State of White America, 1960-2010

The destruction of a unified white majority

Welcome to this week’s edition of the Write & Lift, no-read Book Club. We’ll be discussing Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010.

If you would like to get access to book club essays and join our weekly discussion group on Saturday, upgrade your membership below. For paying members, the link to this week’s meeting is at the bottom of the essay.

Dangerous Book Club: Coming Apart, The State of White America, 1960-2010

In Coming Apart, author Charles Murray draws on over five decades of data and research to make the case that America’s white population has become fractured, disillusioned, and economically stagnant. This of course, is not good.

Murray is not adopting a racialist perspective (attempting in any way to disparage or downplay the contributions to American society by blacks, asians, or hispanics) rather, he shows that the social and economic mobility of white Americans is an indicator of the overall health and stability of the culture and economy.

There is plenty of “myth-busting” in Coming Apart. In part, this is to address the immediate skepticism that some may have toward caring about white interests at all. While America has always been a heterogenous society — the early colonies consisted of Quakers, Protestants, Catholics, Irish, French, Welsh, Scots, etc… — the American “melting pot” identity we’ve been sold as our timeless modus operandi is largely a 20th-century lie.

Today, we think of Italians, Irish, German, and English as different branches on the tree of European “white”. This was not always the case. Italian and Irish Catholic immigrants faced discrimination and loss of opportunity in Northern Cities in much the same way free blacks did. Germans were distrustful of Swedes. And English were distrustful of Scots. Over time, this tension withdrew, and a homogenous “white” identity — divided slightly by cultural history and religious practice — became the backbone of American industry and political power. The influx of immigrants through the early 20th century did not come from South America, the Middle East, India, or Africa. An overwhelming majority were “white” Europeans. White European immigrants, like Africans or other peoples, began to see themselves as part of a larger diaspora within the United States. A European identity became swapped with self-identification as an “American”. And within these separate clades of immigrant communities, a national “white” identity was born. This white majority, which had remained the backbone of American social and economic power since the nation’s founding, would begin to diminish with Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This act removed barriers to immigration from Asian, South American, Middle Eastern, and Eastern European countries. This marked a significant shift in the American social and cultural landscape. Immigration policy before the signing of the 1965 Act, remained highly selective — one could even say discriminatory — choosing only the best and brightest out of the huddled masses waiting for American citizenship. This was a reasonable immigration policy. Selected immigrants were generally well-educated, hard-working, and ready to buy into the established white American culture that had galvanized the progress of the nation to the heights of the world stage in less than 200 years.

This would change in the coming five decades. A combination of increased “third world” immigration, technological change, and social unrest, would divide a culturally unified white demographic.

The White Divide

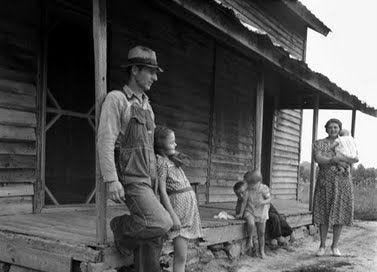

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, very little separated upper-class and lower-class whites. Upper-class whites would vacation alongside lower-class whites at the Finger Lakes in upstate New York. Both classes shared membership to local philanthropic organizations like the Lion’s or Rotary Club. Both classes shared similar tastes and interests in literature, music, and entertainment. Both classes attended Church services together and both classes ate a similar diet.

Of course, there were minor differences between the rich and working class— an upper-class white may donate money for the construction of a new community library while a lower-class white would initiate a donation drive — but both shared the same or similar, religious and cultural identity. Murray shows that the gap between the white upper and lower classes was much smaller. To illustrate this point, Murray discusses the rise of the “super zips”; zip codes where an overwhelming majority of the population is in the top 1% of wealth.