Welcome to the third edition of the Write & Lift, no-read Book Club. If you would like to get access to book club essays and join our weekly discussion group on Saturday, upgrade your membership below. For paying members, the link to this week’s meeting is at the bottom of the essay.

The Black Hole of Violence

Blood Meridian is unlike any book of fiction I have ever read. The prose is swirling, biblical, hallucinogenic; otherworldly. Both chaotic and deliberately slow. Cormac McCarthy; like Faulkner, Hemingway, and Steinbeck before belongs to the pantheon of great American writers. But it’s no surprise why he is often looked over. Few have the courage or moral fortitude to explore the underbelly of human nature as McCarthy does.

There is a horrific familiarity with the themes and prose of McCarthy’s work. Three of McCarthy’s novels, “No Country for Old Men”, “The Road”, and “All the Pretty Horses” have been adapted for the big screen. But Blood Meridian, which has been called “the great American Novel” of the 20th century, has remained an elusive project for filmmakers.

Blood Meridian is McCarthy's fifth novel. And while it’s hard to get through at times, it is harder to ignore. It is a must-read for anyone who desires to acquaint themselves with the great works of American fiction.

The rhetorical beauty of the book comes primarily from McCarthy’s use of polysyndeton; a literary technique where a sentence is continued through the use of a conjunction like the word “and”. Combined with his archaic and descriptive word choice, this creates a poetic stampede of images and emotions in the language. Take for example this sentence where he describes a band of Apache raiders:

“A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners, coats of slain dragoons, frogged and braided cavalry jackets, one in a stovepipe hat and one with an umbrella and one in white stockings and a bloodstained wedding veil and some in headgear or cranefeathers or rawhide helmets that bore the horns of bull or buffalo and one in a pigeontailed coat worn backwards and otherwise naked and one in the armor of a Spanish conquistador, the breastplate and pauldrons deeply dented with old blows of mace or sabre done in another country by men whose very bones were dust and many with their braids spliced up with the hair of other beasts until they trailed upon the ground and their horses' ears and tails worked with bits of brightly colored cloth and one whose horse's whole head was painted crimson red and all the horsemen's faces gaudy and grotesque with daubings like a company of mounted clowns, death hilarious, all howling in a barbarous tongue and riding down upon them like a horde from a hell more horrible yet than the brimstone land of Christian reckoning, screeching and yammering and clothed in smoke like those vaporous beings in regions beyond right knowing where the eye wanders and the lip jerks and drools.”

All men in Blood Meridian possess a lust for blood and violence, positioned within an unknown layer of hell that Dante himself would have struggled to imagine, the “meridian” from which their lives and civilization itself will fall. War and violence in Blood Meridian is a civilized ritual beyond morality for the characters, but not for the writer, who forces his readers to evaluate the characters' moral and philosophical stances.

Blood Meridian follows The Kid, a nameless boy who escapes from an abusive home in Appalachia and finds himself on the Texas-Mexico border in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. In time, the Kid becomes a member of the outlaw Glanton gang, with a majority of the novel detailing the gang’s exploits in the expanse of the desert wilds of Apache territory. Tasked initially with protecting the small Mexican towns in the surrounding area from Native raiders, the Glanton gang becomes increasingly violent. Torturing and scalping Apaches, raising the Mexican villages they’re sworn to protect, and gunning down militias traveling through the region. The Kid becomes baptized into the worst shade of human nature and matures in an orgy of violence and destruction.

I will not waste any of your time spilling details about intricate plot details — it would be unfair to the genius of McCarthy even to attempt it — I will only say that Blood Meridian is a story of escalating violence. This world is unbound by any sense of normalcy; where a philosophy of the law of nature and the primal thrill of killing become its foundational tenet. What happens to man when he behaves like a predator? What kind of moral code justifies such an existence?

The Kid — nameless throughout the story — is all of us. A crude survivalist. A pragmatic animal when necessary. A type of anti-western narrator with the punctuated speech of the B-movie Western villains we grew up watching. Looking at a severed head, '“he spat and wiped his mouth. He ain’t no kin to me, he said.” A victim of cruel circumstances. Bent towards the scraps he can claw away for his preservation from any of his fellow men. A wanderer as they are, coming of age in cruelty and malevolence.

“The truth about the world, he said, is that anything is possible. Had you not seen it all from birth and thereby bled it of its strangeness it would appear to you for what it is, a hat trick in a medicine show, a fevered dream, a trance bepopulate with chimeras having neither analogue nor precedent, an itinerant carnival, a migratory tentshow whose ultimate destination after many a pitch in many a mudded field is unspeakable and calamitous beyond reckoning.

The universe is no narrow thing and the order within it is not constrained by any latitude in its conception to repeat what exists in one part in any other part. Even in this world more things exist without our knowledge than with it and the order in creation which you see is that which you have put there, like a string in a maze, so that you shall not lose your way. For existence has its own order and that no man's mind can compass, that mind itself being but a fact among others.”

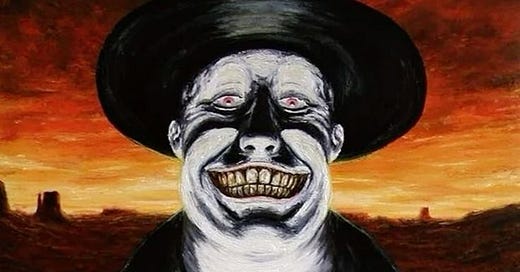

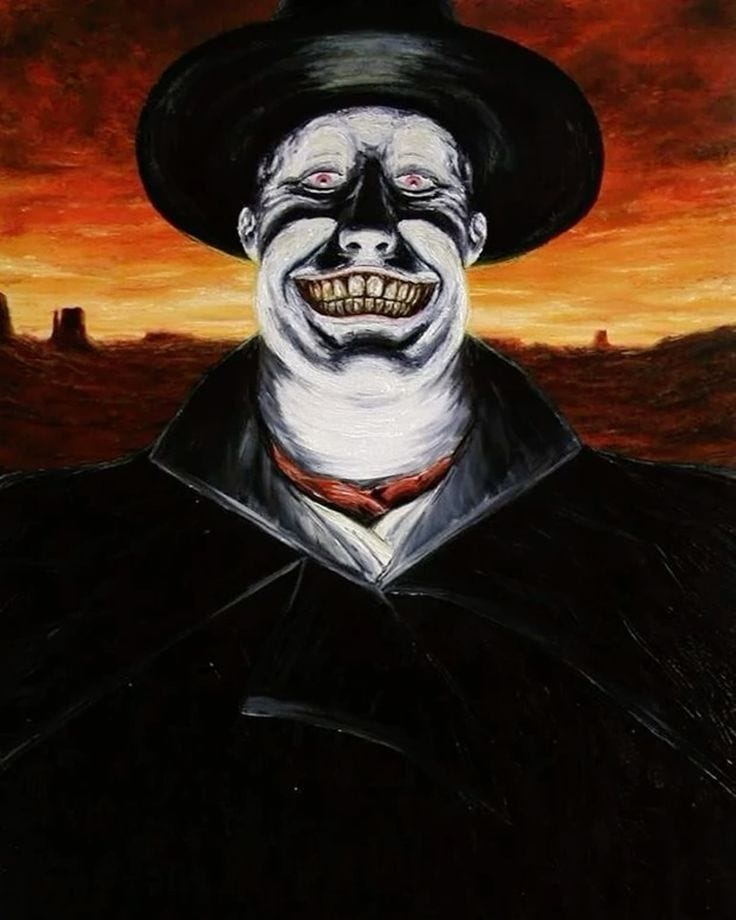

At the beginning of the novel, The Kid wanders into a religious revival tent where a man named Reverend Green is preaching about the nature of death and hell. As he watches the preacher, a huge man (seven feet tall) comes into the tent and starts making serious accusations about the reverend. The tall man, who has albinism and a broad and bald anvil-shaped head, claims the reverend is a fraud with no credentials and — worse yet — a rap sheet that includes sexually assaulting a goat. The townspeople crowd around the reverend feeling thirsty for his blood while the kid ducks out of the tent. That evening at a bar, The Kid watches as men of the town crowd around The Judge where he drinks and holds court. He reveals that the accusations against the preacher were made up. Thus the reader meets The Judge, the primary antagonist of Blood Meridian.

After weeks spent wandering in the desert after killing a bartender in a knife fight, The Kid gets picked up by an American expeditionary group operating extrajudicially in the aftermath of the Mexican-American war on the border. The leader of the group, Captain White, fixes up The Kid and gives him a horse and a gun. Soon after, their group is attacked by Apache’s with only The Kid and a man named Sproule surviving. After scraping by on little food and water in the desert the two make it into a Mexican village where they are both promptly arrested for being part of the American expedition. That night in jail, The Kid recognizes a man from the Glanton Gang he’d scrapped with in St. Louis and eventually joins the gang when he’s freed.

While the gang is named after the wandering John Joel Glanton, The Judge — Glanton’s chief lieutenant — is the spiritual head of the gang and serves as the spark for the gang’s increasing violence. The gang is commissioned to take Apache scalps along the Rio Grande but their sadism evolves toward the ritual killing of innocents.

The Judge

The Judge is the most important character of the novel. He is a character beyond evil. He is not a cunning and satanic trickster, he is a god of violence, the Devil’s general of war sent to earth to convince men to embrace their ‘ultimate trade’.

“When the lambs is lost in the mountain, he said. They is cry. Sometime come the mother. Sometime the wolf.”

-The Judge

McCarthy is aware that the reader will attempt to rationalize and understand The Judge’s action. But the point of The Judge character — at least how I interpret it — is that he represents a type of undefined evil and darkness that lives beyond the rational evil and violence men pursue out of war, passion, and anger. The Judge acts without a moral code. Without justifying his actions. He simply kills and moves on.