Write & Lift is an ethos of personal and spiritual development through conscious physical exertion and practice of the writing craft. Through this effort to strengthen our bodies and minds, we become anti-fragile and self-respecting sovereign individuals. Through this effort, we may stand against untruth and evil and create a new culture of vitality, strength, and virtue.

God Sized Hole

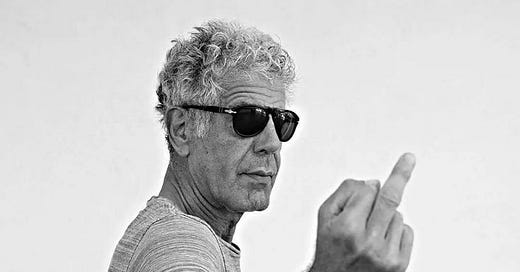

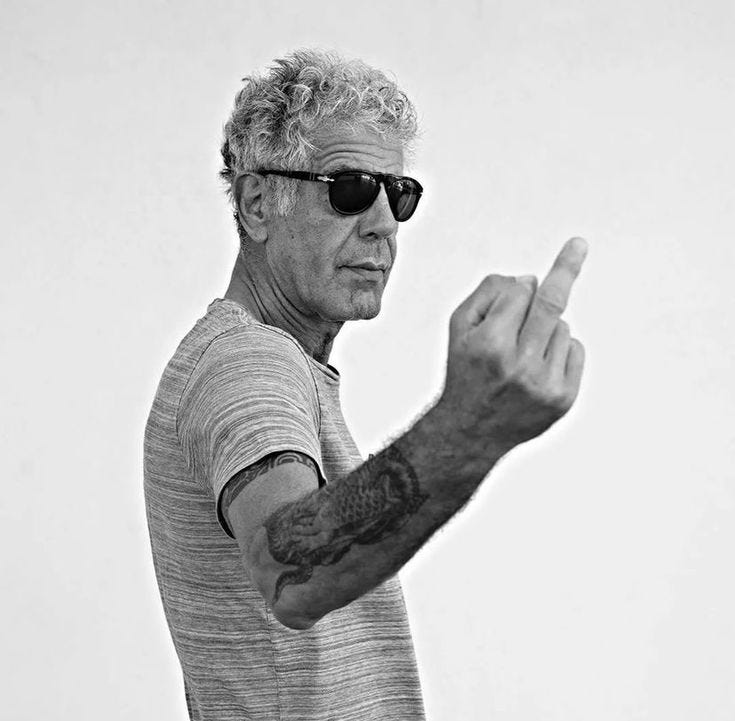

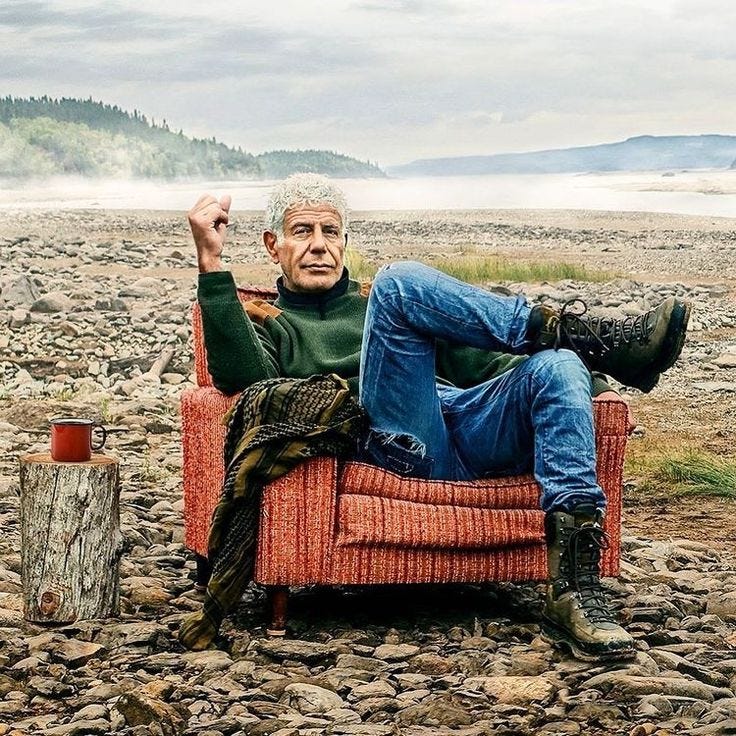

It wasn’t until after Anthony Bourdain died that I saw his antagonistic quips about “Americans” and the deluded masses’ aversion to realness for what they were. He was, I believe, telling on himself. A desperate romantic with a desperate sense to see an unknowable truth in the world. After a while, you cannot avoid seeing the mirage for what it is, and Bourdain, despite trying as best as he could to curate realness himself, was led astray.

I don’t want to spit on the man. I like him in the same way I like an old friend trapped in bad habits. Bourdain needed to maintain some punk rock animosity toward the world to preserve its mystery. He makes the same mistake as most Romantics. Underneath the so-called “mundane” reality of our day-to-day lives and places is a “gritty truth” occupied by the naysayers, dissidents, and outlaws—preserving these vestiges of “realness.” Now, that’s the mistake.

Rewatching Parts Unknown and No Reservations in the aftermath of Bourdain’s suicide, it’s most notable to see what isn’t included.

In studying a cult of personality like Bourdain—a martyr for “authenticity”—one can see, with clarity, the blindspots we’ve all neglected. Some say he died for something: an annoying old chef I worked with described it as a “weight of seeing people for what they were.” I think he died because he had nothing to live for. He died for nothing. If this sounds callous, consider what the man himself had to say:

“Assume the worst. About everybody. But don't let this poisoned outlook affect your job performance. Let it all roll off your back. Ignore it. Be amused by what you see and suspect.”

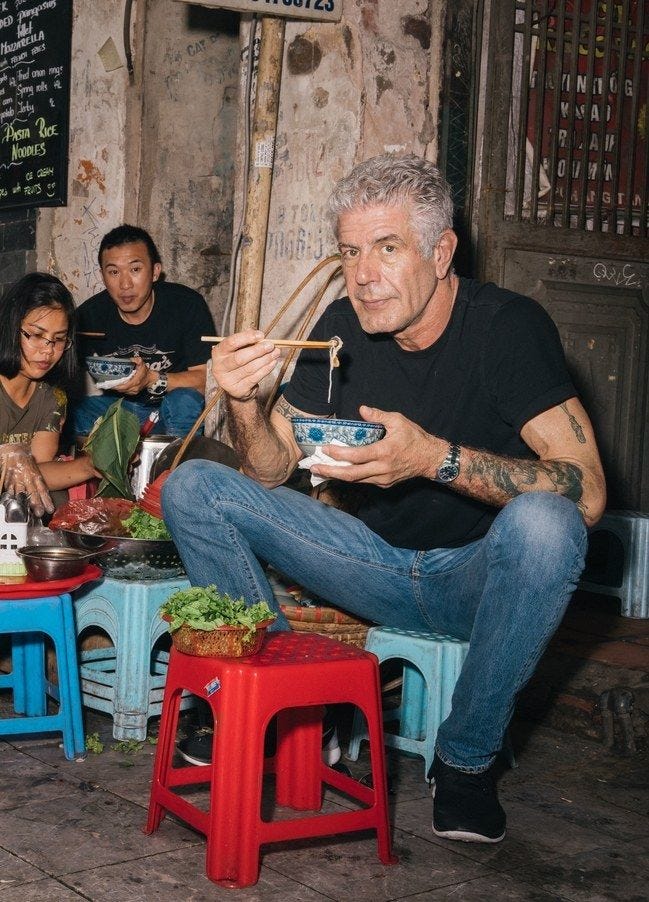

No amount of pho broth slurping on a Vietnamese street corner can save a world beyond redemption or alter a bleak and machiavellian sense of personal relationships. This is the cynics’ paradox. If there is nothing truly to live for, then what must be worth living for is the act of living itself. In short, pleasure, “experiences,” drinking, and chopping it up with CNN-placed “local experts” for small talk over oysters and vodka.

One can catalog all the shades of human experience and still find nothing without having an engrained sense of moral truth, beauty, and righteousness. For Bourdain—for most of us—the revelatory meaning in these three words (and remember, words must speak to something specific to mean anything at all) is often soul-crushing, so much so that we’d be stupid to entertain their implications. Doing so invites the darkness of ego death and the weight of a thousand lived-lies.

Maybe Bourdain would say he conceptualized these things. I cannot be sure. But actions speak louder than words. If it looks like an alcoholic, drinks like an alcoholic, and rationalizes like an alcoholic, it’s still a damn alcoholic. Bourdain killed himself many years before June 2018.

Another Bad Boy

“When I die, I will decidedly not be regretting missed opportunities for a good time. My regrets will be more along the lines of a sad list of people hurt, people let down, assets wasted and advantages squandered.”

- Anthony Bourdain, Kitchen Confidential

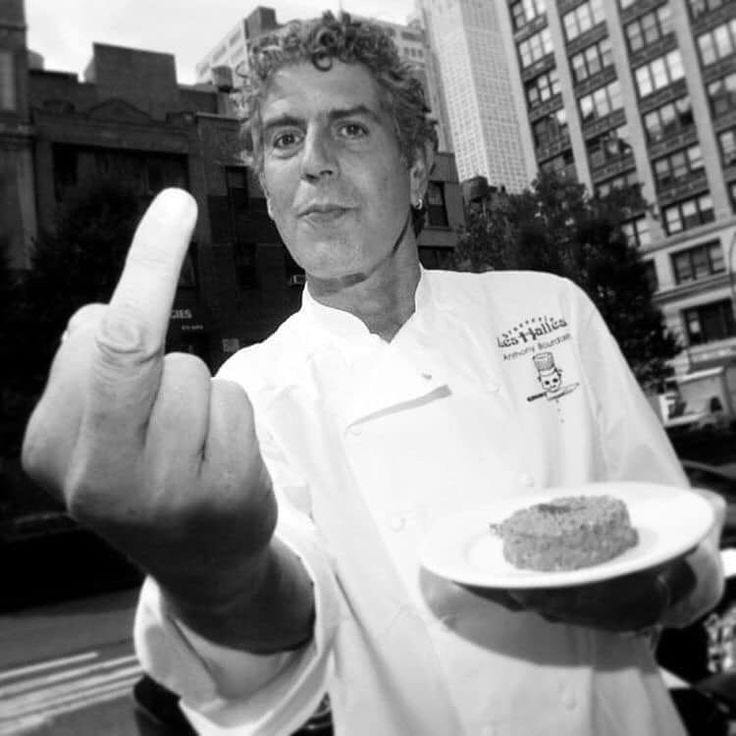

Anthony Bourdain was not an original media figure in the way many have assumed. He was the food version of Hunter S. Thompson, Kurt Cobain, and Banksy; the rebellious “outlaw” who becomes simultaneously steeped in praise by the machine he claims to oppose. There are some real cruel accidents of fate (I once read about two Siamese twins who shared one lower torso while only one was gay), but Bourdain’s self-referential and contradictory persona was manufactured out of necessity. He wasn’t a victim. He was a willing participant, becoming one more misanthropic martyr for the narcissistic “humanity is fucked man” philosophy that he embodied.

This is apparent in Bourdain’s dismisal of his wealth:

“I think money is shit. You know… how much you spend on a thing… If I spend a couple thousand dollars on sushi for two, I don’t feel guilty about that. I do find that my happiest moments on the road are not standing on the balcony of a really nice hotel. That’s a sort of bittersweet—if not melancholy—alienating experience, at best. My happiest moments on the road are always off-camera, generally with my crew, coming back from shooting a scene and finding ourselves in this sort of absurdly beautiful moment, you know, laying on a flatbed on those things that go on the railroad track, with a putt-putt motor, goin’ across like, the rice paddies in Cambodia with headphones on… this is luxury.”

Let’s take what he’s saying at face value. Having money is shit. Certainly having no money is shittier, right? Laying on a dangerous flatbed train and cruising through jungle, rice paddies, and peasent hovels might have been Bourdain’s idea of self-indulgent luxury, but is it anyone else’s? This isn’t an argument about “privilege”—quite the opposite—my distaste for Bourdain isn’t that he made money and chose to travel, it’s that his self-styling as a renegade writer fighting cultural entropy is laughably stupid. We all say things we wish we could take back, but Bourdain’s soliloquies read more like the disenchanted ramblings of a 20 year old backpacker than that of a worldly travel host, entrepreneur, and fine dining chef. It’s possible that the feeling of excitement he felt at that age imprinted on him and never let go.

Selective Outrage

In an episode on Quebec, Bourdain dines with a fellow chef who toasts the Queen of England. Bourdain smirks and holds his glass away, saying; “I hate the aristocracy man.”

When you’re not paying attention to the food and well-shot scenery, you start to realize that ignorant disdain is one of Bourdain’s casual shticks. Like an indoctrinated college sociology student, Bourdain would, of course, claim to uphold this rude behavior on account of “principles” but you never get a sense of what those principles are. A fear and dislike of authority? That figures. Most chefs are assholes and, having worked under asshole chefs myself, I can relate to a general “fuck authority” attitude. Hating the late Queen of England sounds silly and banal, but it’s not. It’s a litmus test. The French Canadian gentlemen isn’t toasting up the Queen because he feels a sense of moral obligation, he’s doing so as a sign of respect to himself and his culture. The natural response for most of us were we sitting at this table, would be to inquier about the historical and cultural relationship between the Quebecois and the British monarchy. That would interest most of us, no?

In his travels, Bourdain sought out the “dissidents” who he saw as analogous to himself; activists, journalists, creatives, and musicians. He ate their traditional food, walked through their ancient streets, and swallowed the curated (and legitimate) opinions of his handlers. Many of these people are fascinating in their own right, but they don’t appear on screen at the roll of the dice. They’re there, in part, to confirm Bourdain’s bias. The casual tourist, in talking to random people at a pub is more likely to get a real “sense” of a place in this way. The angles of almost every epsiode of Parts Unknown and No Reservations almost exclusively being that of “change” due to authoritarian or social pressure. I’m painting with a broad brush, but if you’ve seen either show, you get the gist of what I’m talking about. On the occasion where someone casually pushes back on Bourdain’s line of questioning, his tendency to double down on his presumption leads to minor irritation on the part of both. Again, this didn’t happen often because I don’t think Bourdain wanted it to happen.

Notice what Bourdain omits: religion, family, and a fair representation of opinion alternative to his own. In his 2014 Russia episode, he speaks with two political dissidents and a member of the band “Pussy Riot”; whose brand of “activist punk” consists of stunts like stripping in an Orthodox Cathedral and calling the Moscow Patriarchate a bitch. Whether or not you like Putin as a westerner is neither here nor their; wouldn’t it be a more interesting story to learn why the Russian people overwhelmingly support President Putin?

While I have not travelled internationally like Bourdain has, the gift of travel comes from speaking with many different types of people of many persuasions. How would I attempt to understand “Russia” without first attempting to understand the importance of Eastern Orthodoxy? Do dissident punk-rockers who perform crude stunts provide a window into the Russian soul. I think not.

Although Bourdain appreciates the “authentic” and “traditional,” he romanticized the same rebellious and individualistic streak that defined himself. In a cruel irony, his inability to “turn off” his Americanness, led him to viewing the outside world through the lens of outliers of a similar disposition. This came at the expense of real discussion on the virtues of cultural preservation and resistance to modernity's homogenizing forces. Touching on a traditionalist perspective would not only have made for better TV, it would have been more honest. Globalization, urbanization, and consumerism are omnipresent and all-consuming entities. The reason that people respect the English Crown is because it’s a preserved piece of tradition, history, and communal stability. By existing in its diminished state, it’s still providing a tiny bulwark against the forces of cultural entropy that turned Bourdain’s stomach. We can see it, but he couldn’t.

In Retrospect

When you rewatch Bourdain’s adventures, you can’t help but feel the God-sized hole eminating from him. As I said in the beginning of this essay, I don’t want to spit on the man. He occupies a place in the American mythos for a reason. He’s a stylish writer with a good wit. Hell, I would enjoy getting a beer with him.

But in the wake of his death, it opened a lot of us—myself included—to the spiritual malaise of the modern anti-hero persona. I couldn’t tell you what Bourdain lived for, because I don’t think he could either. It’s easy to be a punk rock nihilist and stand for nothing. It takes actual balls to stand for something. Behind his prose and cynical retorts is a man who couldn’t take the pieces of the world he’d experienced and filter them into something true to himself. His writing serves as evidence

“Your body is not a temple, it's an amusement park. Enjoy the ride.”

“Maybe that’s enlightenment enough: to know that there is no final resting place of the mind; no moment of smug clarity. Perhaps wisdom...is realizing how small I am, and unwise, and how far I have yet to go.”

“The journey is part of the experience - an expression of the seriousness of one's intent. One doesn't take the A train to Mecca.”

For Bourdain, the journey is all there was to life. There is no sanctity in prostrating oneself in prayer in the holy city of Mecca or any other santified place. There is no final destination or grounding moral arc to the world.

The fact that Bourdain had a daughter, makes his suicide all the more tragic and selfish. A harsh lesson, repeated many times over.

As always, thanks for reading.

-Joe

I think this is probably spot-on. Bourdain was more productive, creative, and charismatic than 99.9% of the people with his mindset... but he may have also been more authentic. Some worldviews require a measure of cruelty or delusion or hypocrisy to be sustainable. Perhaps Bourdain simply lacked certain traits to the requisite level.

This is the lesson that the culture denies: satisfying desires and taking vacations and earning money and dating beauties won't bring you any closer to happiness. Unfortunately, our entire civilization is now based upon that misapprehension. RIP AB

Bourdain was popular because his embodied disillusionment and search for authenticity are trademarks of the times. Nietzsche criticized Christianity for their preference of a fantastical Heaven, the “Hinterwelt”, as a means of transcending a reality which once reeked of death. The dystopian utopia of modernity has virtually replaced the need for heaven, yet people are more broken than ever before. Today, bliss is found in its opposite: we are born in an artificial simulacrum and seek to escape it in nature, the “Hinterlands”. This is why the modern Church rarely talks about the afterlife, because it doesn’t sell like it used to. The modern church needs to be completely immersed in reality as a selling point because most are not. Christians were instructed to be in the world but not of it; today, people are of the world but not in it.