Welcome to today’s edition of Write & Lift.

If this is your first time reading, subscribe here.

One quick thing:

The fourth Write & Lift Book Club Podcast, featuring writer, artist, and social critic Megha Lillywhite, is live. You can listen to the episode here or anywhere else you get your podcasts. Paid subscribers will have access to all weekly episodes and bonus episodes. Free subscribers will have access to certain episodes periodically.

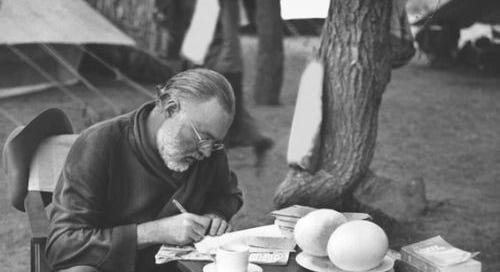

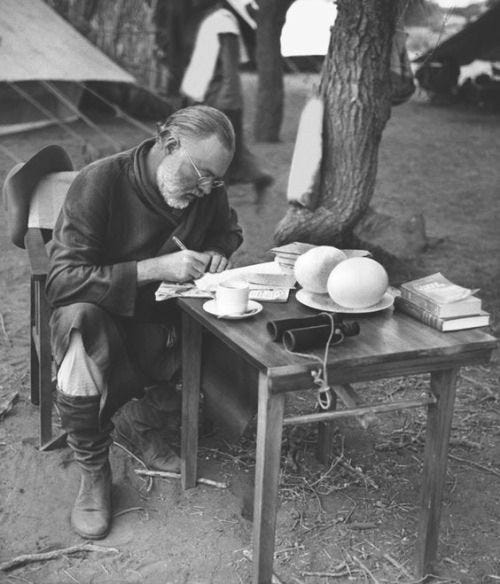

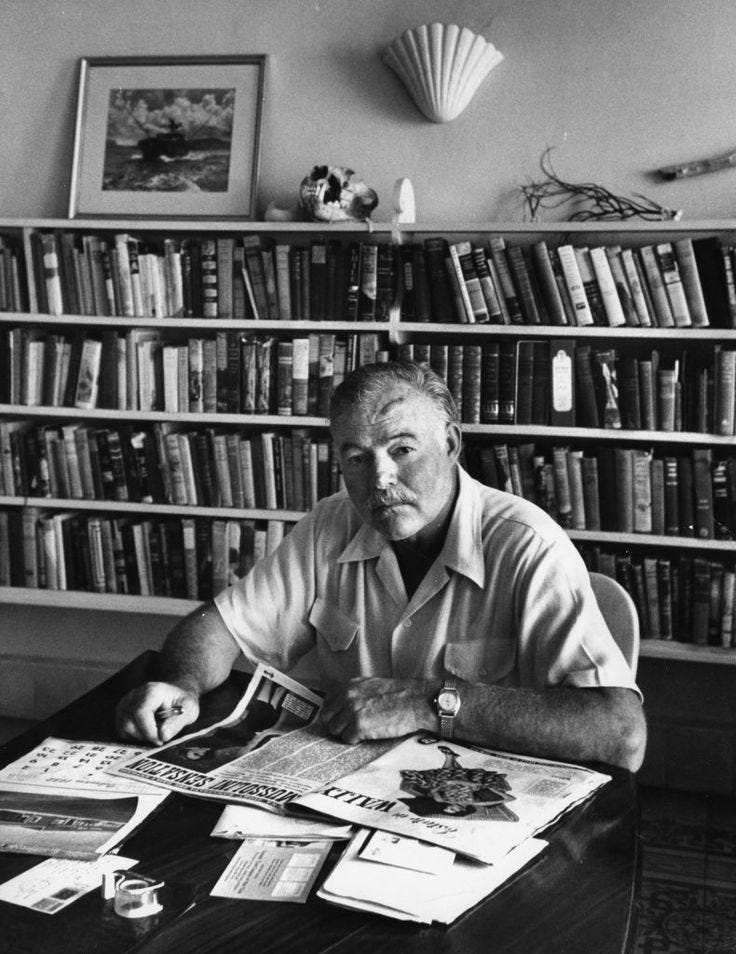

Hemingway’s No Bullshit Rules For Writing

I admire simplicity.

There’s an entire cottage industry of self-help books and podcasts designed to give you the winning framework to become the 1% in whatever you do. Most of these ideas are bullshit.

It’s easy to give complex creative advice that has worked for you. But how applicable is this information to someone with different brain chemistry, habits, and interests? I often ask myself what Charles Bukowski or Hunter S. Thompson would think about the “Andrew Huberman-ification” of productivity and creative output.

I don’t want a set of productivity hacks. I don’t need a complex framework. I want to understand what I’m getting into. I want to learn from someone who has been to the dark place and come out the other side. I want to develop my own toolkit, not plug and play someone else’s idea of a perfect system.

Like is prose, Ernest Hemingway’s writing advice is stripped down and simple. It’s the type of advice you might get from your Grandfather. And this is why I wanted to share it with you today.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a creative, an entrepreneur, or an athlete. Simple, good, advice is cross-dimensional.

1. It’s okay not to get it right the first time

The urge to “create a masterpiece” has left tens of thousands of writers in analysis paralysis hell. Writing classes and MFA programs nationwide are filled with grand ideas for the next great American novel. But how many of these idealists are willing to be honest with their ability? How many of them are willing to suck?

Fundamentally, writing is about engaging with your subconscious. Listening to the dormant and sealed-off parts of your mind that whisper in the ether: “Maybe this word would work better here. Maybe this idea is the right one.”

This is a relationship that must be nurtured. You cannot trust that this apparition has your best interests at heart. You cannot trust that this apparition has some unprecedented access to the truth of the world that your conscious mind does not.

The willingness to see an idea through; regardless of whether or not it will ever be read by anyone, is how you bridge the gap between your conscious goals and the shadow self you’re not regularly engaged with. Overtime, the gap closes, and that’s when there is a joy in creation. But nothing good comes easy.

“Write and don’t worry about what the boys will say nor whether it will be a masterpiece nor what. I write one page of masterpiece to ninety one pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

2. Don’t expect praise before you’ve actually done the thing—or, actually, don’t expect praise at all

I’m going to be honest. It doesn’t matter if you write the next Brothers Karamazov or Infinite Jest. Your thousand-word masterpiece isn’t going to find a modern audience.

For your creative work to “tap in” to the zeitgeist of the modern world, it needs to be created to be digested by the modern world. Charles Dickens released many of his most famous 19th-century works as periodicals in the weekly papers. This is what the Victorian audience wanted — it’s what they were used to. Would he have preferred a complete work; leather bound and ornately designed sitting in the storefront window? Possibly. But the reason he succeeded while so many of his contemporaries failed wasn’t because he was stubborn, it was because he was adaptable.

For a work to be praised, it must be entertaining and engaging. Most people don’t want to be lectured to or beaten over the head with a highbrow philosophy. This is why contemporary art has been so rightfully vilified. It doesn’t provide anything to the audience. It wants us to ask questions. If the technique was beautifully executed and the image stirred in us a familiar passion or emotion, it wouldn’t need the artist’s layers of post-modern metaphor and symbolism. We would inherently get it.

When you work for yourself instead of the potential applause of an imagined audience, you remember why you create. It is a similar principle to rolling out of bed and going to the gym. Are you exercising to compete at the amateur nationals or are you exercising because it instills in you a sense of self-respect and personal duty?

“You must be prepared to work always without applause. When you are excited about something is when the first draft is done. But no one can see it until you have gone over it again and again until you have communicated the emotion, the sights and the sounds to the reader, and by the time you have completed this, the words, sometimes, will not make sense to you as you read them.”

3. Some days are harder than others

Results come from consistency. You must treat your creative task like you treat any other trained aspect of your life. You brush your teeth, take a shower, eat a meal, and go to the gym without thinking. You have to sit down and do the work every single day.

Each of us has a feral puppy running around in our mind. For some of us, this creature gets out of control. It tears up the house. It shits on the floor. It does what it wants, where it wants, whenever it wants. It’s begging to be controlled, to be led. And it is your job to lead it.

Don’t become addicted to the “good days”. You won’t learn anything about yourself when you fall effortlessly into a flow state. If anything, wish for a day that forces you to persevere. This is where you learn your trade, hone your craft, and grow into someone of competence and respect.

“There’s no rule on how it is to write. Sometimes it comes easily and perfectly. Sometimes it is like drilling rock and then blasting it out with charges.”

As always, thanks for reading.

-Joe