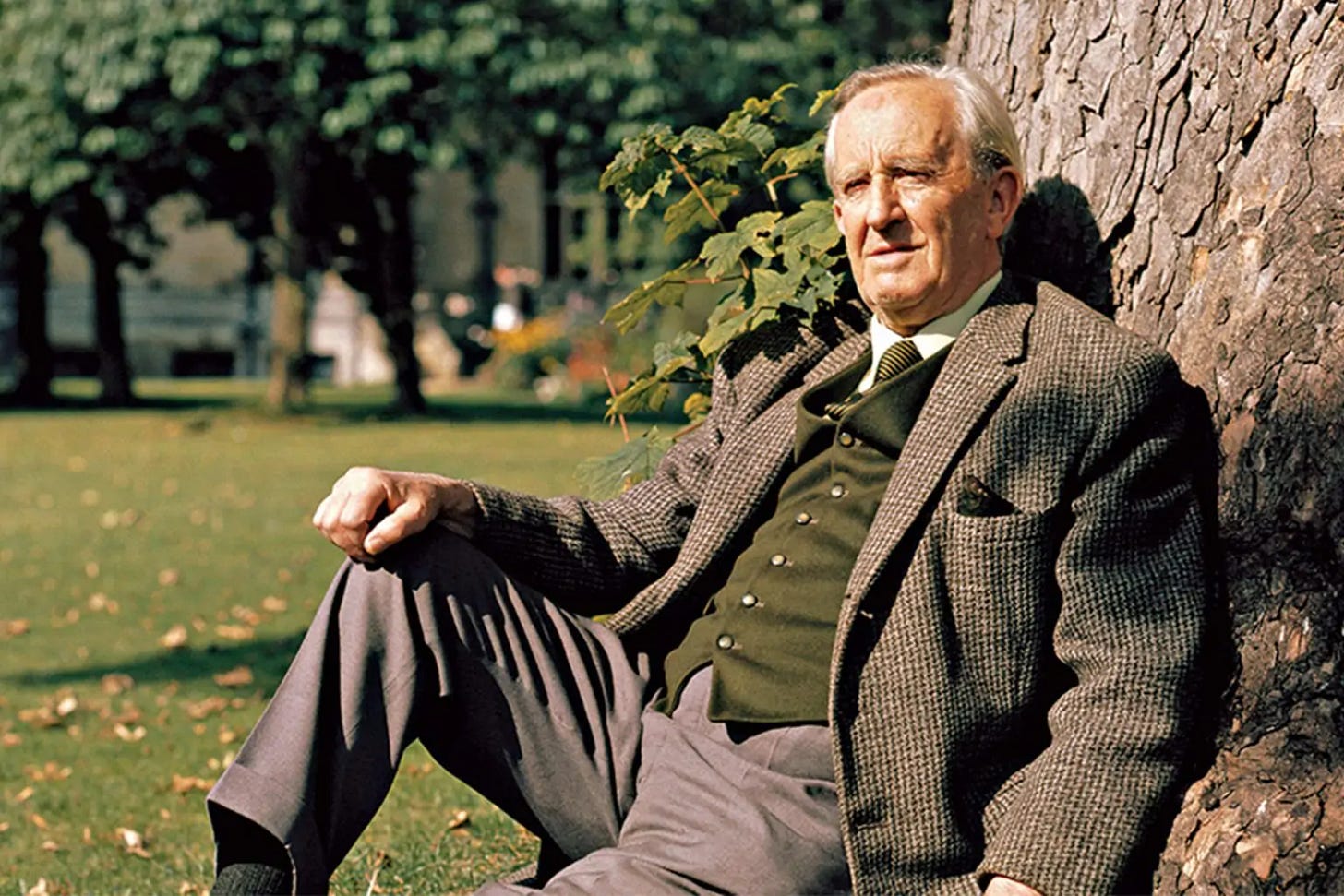

J.R.R Tolkien wrote this in his 1947 essay, "On Fairy-Stories.”

"We have come from God, and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God. Indeed only by myth-making, only by becoming 'sub-creator' and inventing stories, can Man aspire to the state of perfection that he knew before the Fall. Our myths may be misguided, but they steer however shakily towards the true harbour, while materialistic 'progress' leads only to a yawning abyss and the Iron Crown of the power of evil.”

In the heart of darkness, a light always flickers.

This is J.R.R. Tolkien's idea of 'Eucatastrophe'.

Derived from the Greek words 'eu', meaning good, and 'katastrophe', meaning destruction, Tolkien coined this term to denote a "sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur." A sudden turn of events ensuring the protagonist does not meet some terrible, impending, and very plausible doom. Tolkien's idea is not just a random literary technique, it is a bridge between the reader and the divine ideals that undergird our myths and stories.

Tolkien saw 'Eucatastrophe' as the soul of stories and our lives, reminding us that even when all hope seems lost and doom, certain, there's always light. A guiding hand. An unpredictable event that brings hope. We want to believe that good things happen to good people, and Tolkien saw this concept as a representation of the divine light that binds our world together.

To Tolkien, this wasn’t just an element of good storytelling, it's a philosophy. A belief that every dark tunnel has an end. That good always prevails regardless of the hatred, violence, and lack of hope that can swallow the world.

Think of Frodo using the Elven phial in the dark layers of Shelob’s cave. This is that sliver of hope embodied, a reminder to the audience that not all is yet lost.

He described the concept in further detail:

The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous ‘turn’ (for there is no true end to any fairy-tale): this joy, which is one of the things which fairy-stories can produce supremely well, is not essentially ‘escapist’, nor ‘fugitive’. In its fairy-tale—or otherworld—setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.

Joy as poignant as grief.

Why does it feel like this is an antiquated idea in our current media?

Have we lost the ability to recognize the true divinity and beauty of the human spirit?

Can you recall a eucatastrophe in a recent novel, movie, or show you’ve seen?

Regardless of your answers to these questions, Tolkien’s idea can serve as a powerful reminder in our own lives that when we are at our most broken, there is always hope.

These changes to our path, the trials along our journey, often require us to reach a depth of despair and self-doubt we felt was impossible. It is in these moments when we’re most open to the divine good in the world. A call from a friend, an unexpected job offer, or a relationship that rekindles our soul and spirit. For the hero, the eucatastrophe occurs at our darkest moment. It is a sign that the journey up to this point, has not been in vain, and in the darkness of the final test, there is light.

When you have a North Star, a set of guiding principles and morals, this moment acts as a clear signpost. A signal that you also can be an embodiment of the divine. However, if you are convinced that all humans exist in a morally grey soup, this moment can become shrouded.

This is how the eucatastrophe applies to our own lives.

The Moral Grey’s

Over the last decades, there’s been an increased reliance on morally grey characters in contemporary media and stories. These are figures who straddle the line between hero and villain, embodying the reality of the human capacity for both good and evil. This isn’t inherently a bad thing. When these morally grey characters are balanced by what we would call hatable villains and true heroes, they add depth and complexity to the story. But more often than not, these stories are devoid of eucatastrophes simply because there is an omission of any larger moral truth that supports the narrative structure.

Tolkien himself included many grey characters in his stories: Boromir, Gollum, and Lord Denethor, to name a few. But these characters were always balanced between representations of good and evil. This draws the audience closer to the story, as we see the characters being pulled to the magnetic energy of these contrasting and powerful forces.

A good example of another story that balances “grey” characters with an overarching moral truth is the three original Star Wars films.

Luke shows courage, resilience, compassion, humility, and a willingness to sacrifice himself for those around him. He is an archetypal knight, someone that the audience wants to root for. And though he is tempted by the Dark Side, he never succumbs. He is a true hero.

Contrasting Luke is The Emperor. He is manipulative, deceitful, cruel, power-hungry, frightening, and sadistic. He is the antithesis of the hero, the embodiment of pure evil. He is a hatable villain.

Now what makes the original Star Wars trilogy such a classic, is the addition — not domination — of morally grey characters like Han Solo and Darth Vader. These characters are pulled into different directions by those around them, and there is a conflict between their actions and their beliefs. On the surface, they may appear to be good or evil but as the story progresses, their motivations and actions change how they are seen by the audience.

But when these characters dominate the narrative, the viewer can start to be fatigued by what they feel is the lack of pure good and pure evil in the world. In an attempt to present “the moral grey area of humanity”, the story can feel like the entire cadre of supposed heroes and villains are just masked representations of the other side. What’s the point in rooting for the “hero” if he or she is going to lash out in anger and murder someone, or fall prey to the wicked charms of the supposed villain? We want to believe that some of us are — at our core — good people and that in the stories and fables of our culture, these paragons of humanity’s finest traits are ultimately rewarded and represented fairly. While morally grey stories like “House of Cards”, and “Game of Thrones” might entertain or even enlighten us to the moral line many of us walk, they ultimately can leave us feeling hollow and empty. The narrative becomes devoid of clear moral benchmarks and hopeful outcomes.

It is here that eucatastrophe can add depth, purpose, and optimism, and remind us that even in the grey area with which many of us walk, there is still a divine moral truth that binds us all.

Eucatastrophe

This is mind blowing, I can't stop reading