The Writer’s Thoughts

The year is 1945, and a small, quaint town in New Mexico is about to be rocked by an explosion so immense that it will change the course of history.

The Trinity Test, the first detonation of an atomic bomb, is about to begin. Little did the residents of Alamogordo know that their lives were about to be irrevocably altered. The question, my friends, is this: have we learned anything since that fateful day?

Fast forward to today, and the world is still teetering on the edge of nuclear annihilation. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the closest we've ever come to a full-scale nuclear war, saw the world holding its collective breath for thirteen days. We were a hair's breadth away from destruction, yet here we are, continuing to stockpile weapons of mass destruction.

And who can forget the harrowing tale of Stanislav Petrov, the man who literally saved the world in 1983? When his computer falsely reported incoming American missiles, Petrov defied protocol and refused to launch a counterstrike, believing it was a false alarm. His gut instinct prevented an all-out nuclear exchange. Think about it: we were one man's decision away from catastrophe. Is this how we want to live our lives, dependent on the instincts of a single individual?

So here we are, playing with fire as if we haven't been burned before. We've had close calls, but have we really learned from them? Are we just stubborn, or have we developed a sense of invincibility that prevents us from seeing the very real danger we face?

We've signed treaties, made promises, and talked a big game about disarmament, but in the end, the numbers don't lie. There are still more than 13,000 nuclear warheads in existence, and if that doesn't keep you up at night, I don't know what will.

Now, I'm not here to be the harbinger of doom, but rather to urge you to open your eyes to the reality of our situation.

Food For Thought

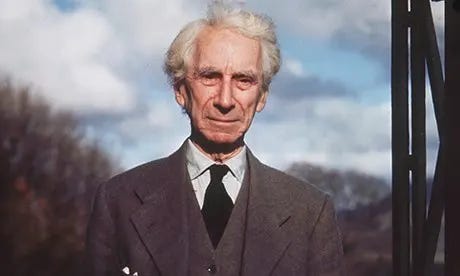

Bertrand Russell |"Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war? People will not face this alternative because it is so difficult to abolish war. […] The abolition of war will demand distasteful limitations of national sovereignty. But what perhaps impedes understanding of the situation more than anything else is that the term 'mankind' feels vague and abstract. People scarcely realize in imagination that the danger is to themselves and their children and their grandchildren, and not only to a dimly apprehended humanity."

Bertrand Russell, a brilliant mathematician, and philosopher was no stranger to the perils of human existence, and his work resonated with the existential crisis brought about by the atom bomb. In his piece "Man's Peril," Russell confronts the reader with a stark choice: either abolish war or face the extinction of the human race. Bluntly challenging our complacency, he questions whether we are willing to sacrifice our sovereignty to avert catastrophe. Russell warns that the term 'mankind' feels too abstract, and we must recognize the very real threat to ourselves, our children, and future generations.Russell's influential 1955 "Russell-Einstein Manifesto" further exemplifies his urgency in addressing the existential crisis. Co-signed by Albert Einstein, the manifesto implores world leaders to consider the consequences of nuclear war, emphasizing that "we have to learn to think in a new way." The manifesto asks, "Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war?" forcing the reader to ponder the gravity of our choices.

Russell's fearless, contemplative approach forces us to confront the existential risks of the atom bomb. He demands that we face the reality of our situation and decide: will we continue down a path of destruction, or will we embrace the challenge of preserving our very existence?

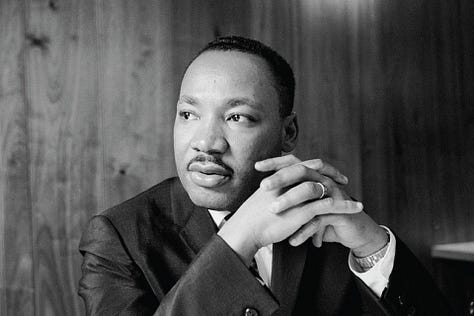

Martin Luther King Jr. | "It is no longer a choice, my friends, between violence and nonviolence. It is either nonviolence or nonexistence. And the alternative to disarmament, the alternative to a greater suspension of nuclear tests, the alternative to strengthening the United Nations and thereby disarming the whole world, may well be a civilization plunged into the abyss of annihilation, and our earthly habitat would be transformed into an inferno that even the mind of Dante could not imagine."

When we think of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., we often conjure images of a fierce civil rights leader advocating for racial equality. But King was also acutely aware of the existential threat posed by the atomic bomb. In fact, his work directly relates to the dangers of nuclear weapons and the existential crisis they present.Take, for example, his powerful words in "Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution" (1968): "It is either nonviolence or nonexistence." King recognized that the choice was no longer between war and peace, but rather between humanity's survival or annihilation. He knew that the development of nuclear weapons had fundamentally changed the stakes, forcing us to confront the very real possibility of our own extinction.

King was unapologetic in his call for disarmament, urging the strengthening of the United Nations as a means of disarming the whole world. Was this controversial? Absolutely. But isn't that exactly what we need in a world teetering on the edge of self-destruction?

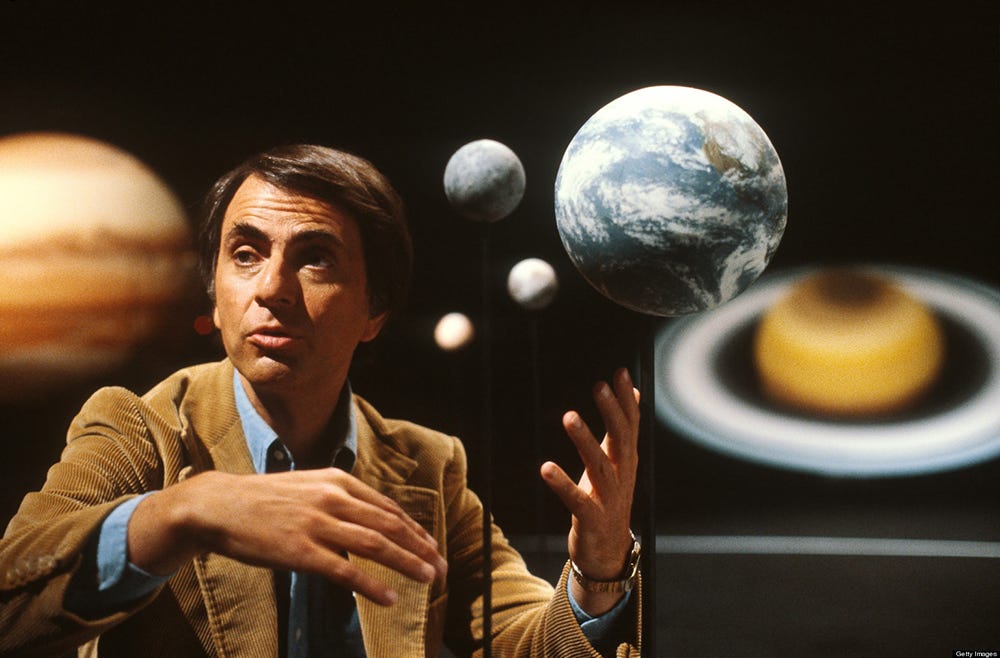

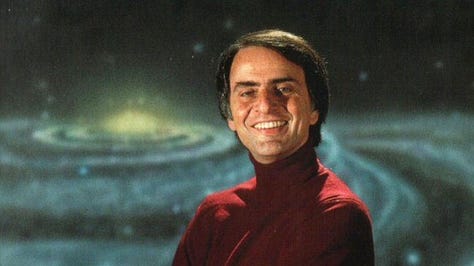

Carl Sagan | "The nuclear arms race is like two sworn enemies standing waist-deep in gasoline, one with three matches, the other with five. [...] The imperative to survive is not just the individual, it's the species. If a dramatic new idea, a powerful new technology, a strong new social institution carries with it the potential for species destruction, it is a danger not only to us, but also to every human being who ever lived and all our descendants."

Carl Sagan, the renowned astrophysicist and science communicator, was no stranger to the existential crisis posed by nuclear weapons. In his groundbreaking television series "Cosmos: A Personal Voyage," Sagan tackled the issue head-on, shedding light on humanity's potential for self-destruction. His work is a clarion call to the world, urging us to recognize the dire consequences of our actions.In the final episode of "Cosmos," titled "Who Speaks for Earth?", Sagan offered a chilling metaphor for the nuclear arms race: "The nuclear arms race is like two sworn enemies standing waist-deep in gasoline, one with three matches, the other with five." With this vivid image, Sagan highlighted the absurdity of escalating tensions between nuclear powers, each poised to ignite a global catastrophe.

In the same episode, Sagan articulated the imperative to safeguard our species' survival, emphasizing that our responsibility extends to "every human being who ever lived and all our descendants." He implored us to consider the gravity of our actions, as the decisions we make today could either ensure our future or plunge us into an abyss of annihilation.

Sagan's work serves as a sobering reminder of the existential threats we face, particularly the looming shadow of nuclear weapons. His powerful, unapologetic message demands our attention and action, lest we ignore the perils of our own making and squander the precious opportunity to secure our collective survival.

The Gallery

Guernica by Pablo Picasso (1937)

Picasso's Guernica, a painting that, though created before the atomic bomb era, captures the essence of the existential crisis wrought by such destructive forces. This masterpiece is a stark reminder of the horrors of war, reflecting the suffering and devastation caused by the bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War in 1937.

But how does this relate to the atom bomb and existential crisis? The answer lies in the raw emotion and chaos displayed within the painting. The contorted, anguished faces of humans and animals alike echo the unspeakable pain that would be inflicted by a nuclear blast. The stark monochrome palette intensifies the somber mood and captures the life-draining consequences of such warfare.

Now, I know what you're thinking: Guernica is about a specific historical event, not nuclear annihilation. But isn't that the point? The painting transcends its original context to embody the universal human experience of suffering and the terror of living in a world where annihilation is a very real possibility. Picasso's Guernica forces us to confront the potential for devastation in the nuclear age, reminding us that the consequences of unleashing such power are not just abstract concepts, but rather tangible suffering and despair.

In a way, Guernica serves as a visual representation of the existential crisis brought on by the advent of the atomic bomb. It's a wakeup call, an urgent reminder of the responsibility we bear as custodians of this dangerous power, and a plea for humanity to choose a different path.