Write & Lift is an ethos of personal and spiritual development through conscious physical exertion and practice of the writing craft. Through this effort to strengthen our bodies and minds, we become anti-fragile and self-respecting sovereign individuals. Through this effort, we may stand against untruth and evil and create a new culture of vitality, strength, and virtue.

The Devil We Choose to See

How we write about evil says more about us than it does about evil itself. I was reminded of this recently while looking at old notes I’d taken while reading Dante's Inferno and John Milton’s Paradise Lost—arguably the two most influential depictions of the devil in Western literature. What struck me wasn’t just how differently these writers portrayed Satan but how their versions of ultimate evil reflected their beliefs about human nature itself.

Most of us carry some mental image of the devil—a red-horned South Park character pleading for the attention of Sadam Hussein, Al Pacino in The Devil’s Advocate, or the hairless, quiet, lingering presence in The Passion of the Christ. Long before Hollywood “modernized” depictions of Satan, these two writers shaped how the Western world imagined and understood evil for centuries to come. Their devils couldn’t be more different: one a frozen, drooling monster, the other a charismatic rebel with a silver tongue. The gap between these portrayals tells us how our view of evil and ourselves has evolved.

What makes us turn against what's good for us? Why do we choose paths we know will lead to our destruction? And most importantly, what does our way of depicting evil say about what we truly believe?

Two God-Fearing Poets

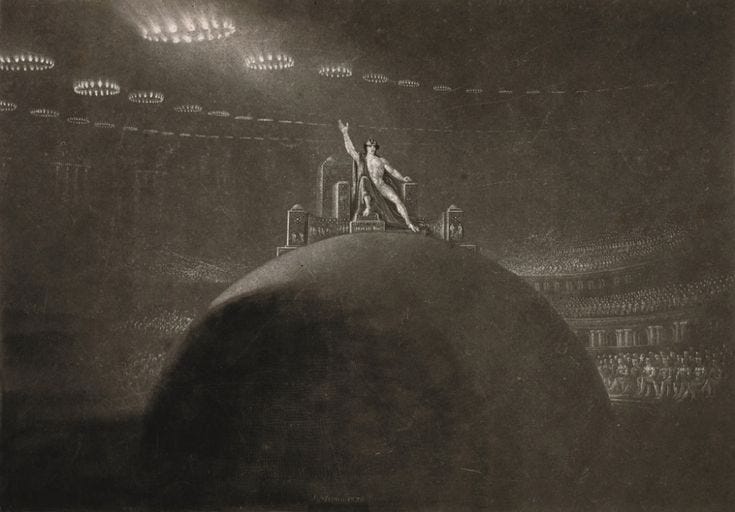

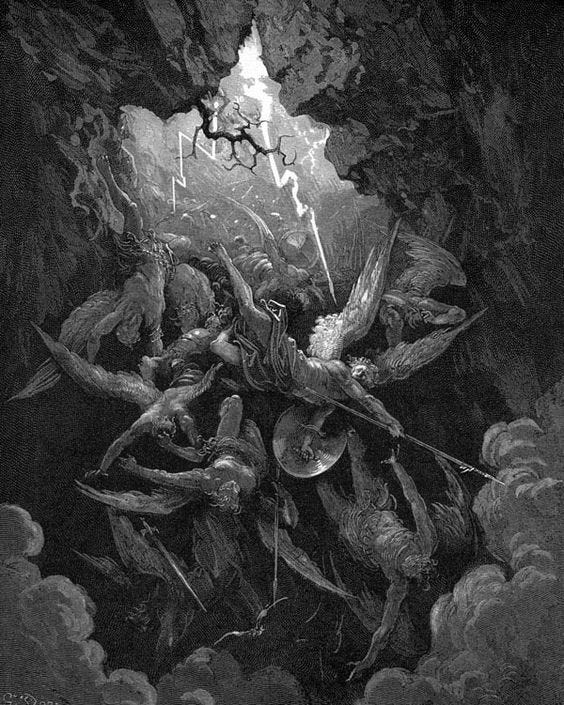

In Milton’s Paradise Lost, the fallen angel Lucifer—who would rather “reign in Hell than serve in Heaven”—speaks to something more profound than mere rebellion. He’s the original silver-tongued villain, the prototype for every self-destructive romantic who chose their path to damnation.

He’s charismatic. He’s clever. He’s intelligent. He makes compelling arguments. When he rallies his fallen angel army with declarations of defiance against God, you feel his energy and power. It’s exciting. It’s galvanizing. Because Milton is playing a deeper game—he's showing us how seductive pride and self-justification can be. His Satan isn't just a “villain”; he’s a mirror.

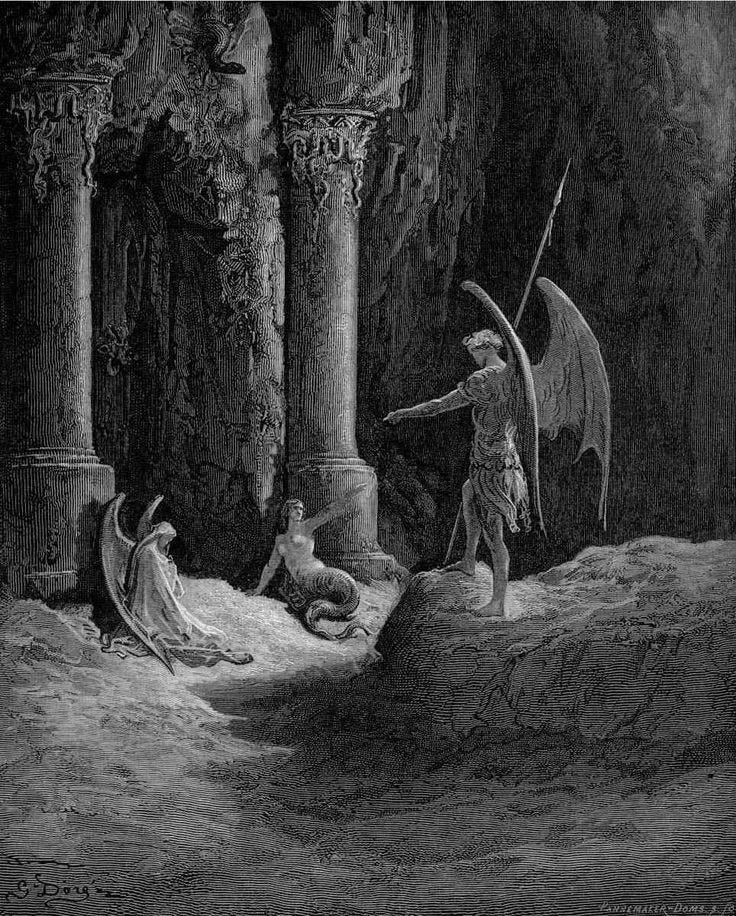

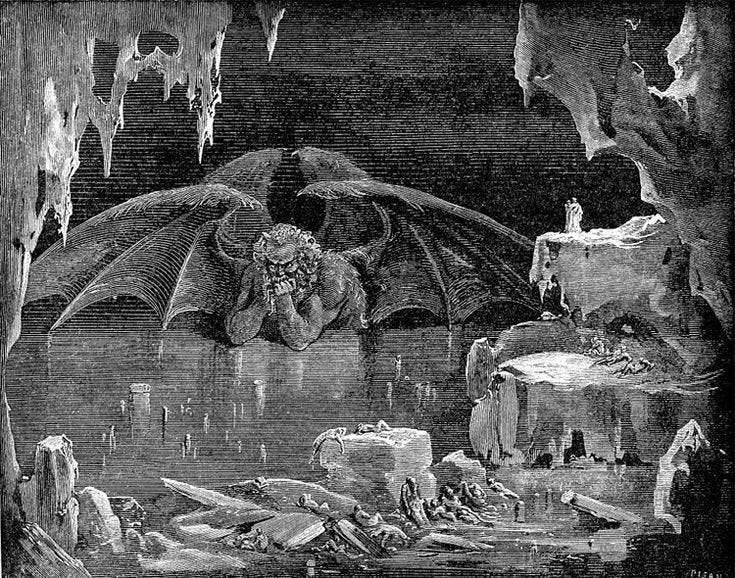

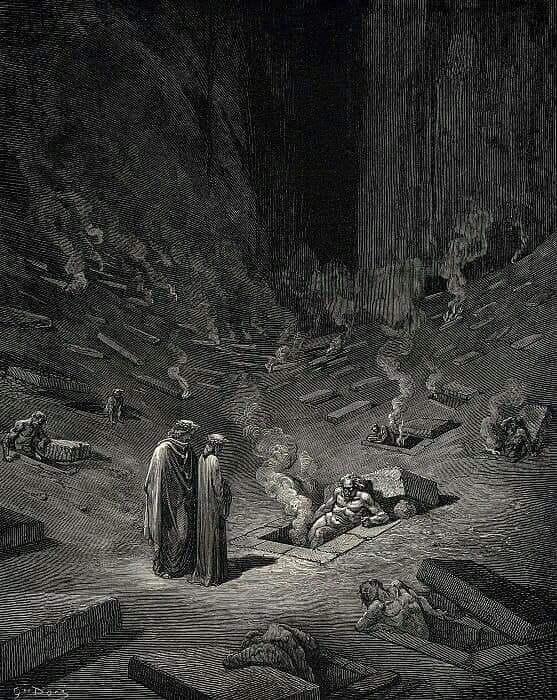

In contrast to Milton’s beautiful and clever “human” Satan, Dante’s Satan is, by design, a grotesque. He’s a frozen, drooling monster stuck in the lowest pit of Hell, mindlessly chomping on history’s greatest traitors like some divine garbage disposal. There's nothing seductive or inspiring about him. He’s not giving rousing speeches or plotting revenge—he can't even move. His three heads represented a perverted trinity: three mouths for the three great betrayers (Judas, Brutus, Cassius), three heads for the threefold nature of sin (ignorance, impotence, hatred). This is what Dante's medieval Catholic worldview saw: evil as pure degradation, stripped of all its seductive power.

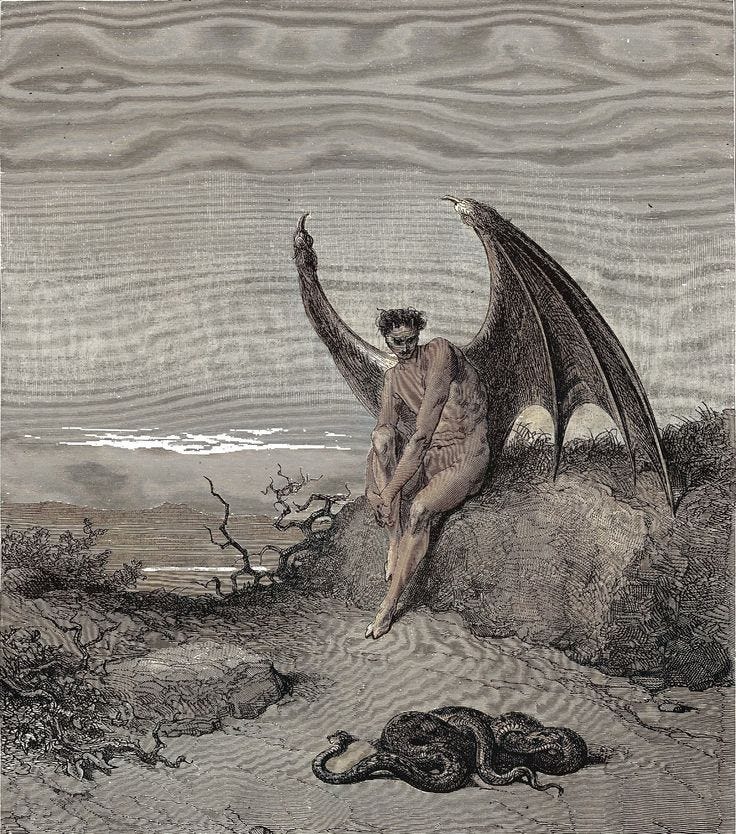

For Dante, evil was simple—a deviation from divine order that must be punished. His Satan reflects this: a pathetic figure, eternally suffering for his crime. But Milton articulated something more disturbing (and more prescient to our current times): evil often comes dressed in heroic clothing, speaking the language of freedom and noble rebellion. His Satan is more than a cautionary tale about pride; it’s a warning about our capacity—and ignorant desire—for self-deception.

In aligning more with Protestant ideas about free will, Milton’s Satan feels closer to our modern conception of evil and sin. This is, of course, a reflection of the times when both men wrote their epic poems. Paradise Lost preceeded the enlightenement whereas Dante’s Divine Comedy predated the Rennaissance. In Dante’s case, late medieval moral codes were hierarchical and enforced through the structure of the Church. It makes logical sense that in Dante’s 14th century representation of Hell, Sinners would be neatly sorted into their appropriate circle based on the magnitude of their sin. In Milton, we get something messier and more psychologically true: the story of someone blindly choosing their damnation and reaping the self-inflicted consequences, all while convincing themselves they’re the story’s hero.

The Devil is Many Things

Both writers wrestle with the same cosmic force of evil while coming away with radically different visions. Their devils are as different as their worldviews. Both are right. And that’s precisely the point.

Milton’s Satan desperately seeks meaning in his rebellion, trying to fill the void left by rejecting divine authority. Unlike Dante’s simple monster, he has the tragic awareness to know what he’s lost, even as he doubles down on his choices.

Dante’s representation of Satan as an ugly aberration shows us that a distance from God reflects in the physical. God gave us a mouth to speak, ears to hear, and eyes to see. When we reject His gifts, it manifests in total disconnect from the world and His beauty. If Milton’s satan looks like something we can more accurately relate to in our modern day, Dante’s Satan shows how it feels internally when we’ve neglected our divine purpose. Together, they represent a picture of the eternal human struggle: the choice between submission to a higher order and the intoxicating allure of absolute self-determination.

We’re all living in the shadow of that original rebellion, choosing daily between serving in Heaven or reigning in Hell. These devils reflect the battles we fight daily in ourselves. Sometimes we’re the charismatic and prideful anti-hero of our story; other times, we’re the monster.

As always, thanks for reading

-Joe

Good reflection. I agree with you that these devils (whatever bodily configuration they may have) are reflected in ourselves when our human desires opt to undertake evil actions. What are those evil actions constitutes a discussion as to what can be classified as evil. I believe God is love and when that love is violated by my actions to not practice that principle with others, it is evil in itself. The seven deadly sins are all evil. All violate the concept of love.