The Mandela Effect

How many false memories do you have?

Welcome to today’s edition of That’s A Good Idea. If this is your first time reading, subscribe here.

One quick thing:

If there is a recent essay or edition that has sparked your curiosity, given you a new idea, or in any way contributed positively to your daily life please consider supporting That’s A Good Idea with a $5 monthly subscription. I want, more than anything for TAGI to remain something you look forward to reading each week and your support helps me to gauge if I am on the right track. While I don’t write to make money, any small contribution is greatly appreciated. Additionally, if there is a specific topic, idea, or book you’ve read recently that you’d recommend me digging into, let me know in the comments below!

The Mandela Effect

What unassailable “truths” are complete figments of your imagination?

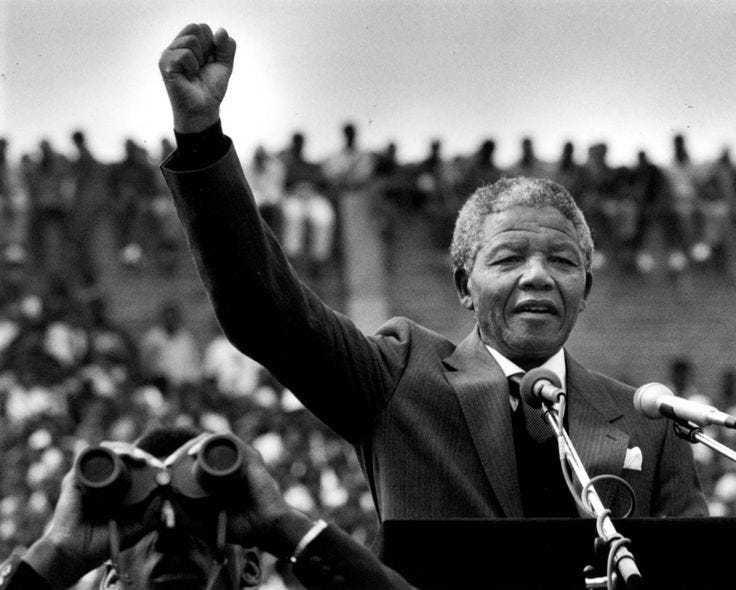

The term Mandela Effect was coined by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome in 2009 when she discovered that many people shared her false memory of Nelson Mandela dying in the 1980s in a South African prison when, in reality, he passed away in 2013.

After she created a website to discuss and document these shared false memories she was surprised to find tens of thousands of others who shared this same false memory.

Broome was awestruck at the depth of these false memories. Posts on the forum documented vivid memories of a national funeral, memories of the “breaking news” of Mandela’s death, and a national day of mourning, none of which occurred.

Over time, the term gained popularity and expanded to encompass various collective false memories that people share, leading to discussions and research about the fallibility of memory, perception, and the quirks of human cognition.

The Blind Spot of Our Mind

Human memory isn’t a perfect recording device. Rather, it is a reconstructive process.

When recalling certain events, our brains fill in gaps or create details according to our biases, moods, and opinions of others. This is what leads to false or distorted memories.

In one example, University of Pennsylvania researchers found that a person’s mood has a significant impact on how they recall early life experiences.

Those who described their mood as bad or negative remembered their childhood less fondly than those who described their mood as positive.

Our brain filters certain information depending on the context of our external and internal environment. During an argument with a friend, family member, or partner, how often does the crux of the conflict come back to one’s perception of an event versus another?

We cling to the idea that our memory is an accurate representation of the past, because to deny that fact, would be to hammer away at the foundation on which our entire lives and concept of self are built.

The Network of “Falsehood”

When a certain idea is prevalent in society, we’re wired to latch onto it. We do this to preserve stats; to avoid being the black sheep. We do this, because we assume, that if enough people believe something it must be true.

This goes beyond a simple lack of exposure to data or information. It’s part of an ancient and subconscious survival network between us as humans.

Just as ants communicate through pheromones to ensure the long-term viability and cooperation of the colony, we communicate through words and ideas.

Challenging a widely held belief, often comes at the cost of in-group preference, treatment, and protection.

While we don’t have the same problems as ancient man, we still have the same programming. We don’t risk being shunned by the tribe for refusing to acknowledge the mythical, animated power of a plant or animal. But we do risk being shunned for challenging prevalent belief systems and ideologies.

For example, where I live in California, a loud majority in my local community supported mandatory closure for small businesses that didn’t abide by the Draconian COVID restrictions.

These same individuals also supported a vaccine passport system to prevent unvaccinated individuals, like myself, from traveling between states.

Now, on local message boards and forums, these same individuals deny that they had called for such measures.

This is an example of the Mandela Effect.

Either these individuals are lying, or, as public perception changed, they began to willfully believe that they had never called for such measures.

Cognitive dissonance represents a type of “noise”, conflicting, and emotional justification in mind. But the Mandela Effect is a replacement of a fact with a more convenient, popular, or seemingly altruistic motive.

Common Falsehoods

Sometimes the Mandela Effect is innocuous; a small detail that becomes so commonly misremembered that we accept the falsehood as truth.

The iconic line from The Empire Strikes Back

“Luke, I am your father.”

Doesn’t exist.

The real line from the film is, “No, I am your father.”

Other pop-culture examples of the Mandela Effect include:

The Monopoly Man: Many recall the Monopoly Man, the mascot of the famous board game, wearing a monocle. However, he has never been depicted with a monocle in the game’s history.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: The line from Disney’s classic film is often remembered as “Mirror, mirror, on the wall,” but the actual line is “Magic mirror on the wall.”

These false memories may arise from cultural factors, media influence, or even random conversations with others. We hear a line enough and simply place a memory “memory” from the iconic scene in our mind.

It shows that our memory, something that we hold closest to us, is not only unreliable but can be shaped by a collective societal narrative.

In the social media age, the Mandela Effect underscores how easily false memories and beliefs can spread, especially when we’re not actively investigating the truth (or when the truth is purposefully obfuscated)

As always, thanks for reading.

-Joe