Welcome to the fifth edition of the Write & Lift, no-read Book Club. If you would like to get access to book club essays, join our weekly discussion group on Saturday, and read the rest of this essay and others like it, upgrade your membership below. For paying members, the link to this week’s meeting will be sent out Saturday morning before the call. Make sure to check your inbox.

If this is your first time reading, subscribe here.

Two quick things:

I’m thrilled to announce that the first Write & Lift Book Club Podcast episode is live. You can listen to the first episode here. Paying subscribers will have access to all weekly episodes and bonus episodes. Free subscribers will have access to certain episodes periodically.

Paid subscribers have access to our weekly “No-Read” Book Club meetings on Saturday, 8:30 AM PST as well as other exclusive essays and book summaries. If you want to become a paid subscriber, upgrade your membership below. If you’re already a paid subscriber, check your email inbox Saturday morning for the Book Club meeting invitation. This week’s group discussion will be focused on the question: “Why do we feel alienated in the modern world?” We’ll be discussing Less Than Zero as well as Jonathan Haidts book The Coddling of the American Mind.

The Truth About Alienation

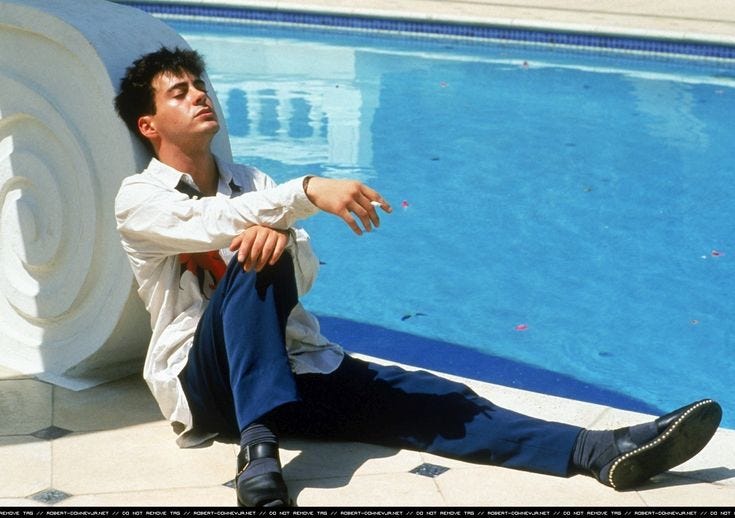

“I don’t want to care. If I care about things, it’ll just be worse, it’ll just be another thing to worry about. It’s less painful if I don’t care.”

-Clay, Less Than Zero

Talk to young people today and many will share the same sentiment: the world is lost, and I’m lost inside of it. A feeling of totalizing disconnection between themselves and others.

The feeling is like when you walk into a party that you thought you’d

been looking forward to going to for a week, and you immediately want to turn and leave.

You feel empty. Untethered. Like some sort of apparition floating from one pointless social interaction to another. The world lost its color and there’s only one way to find it again — to transcend it.

We tend to overcorrect. In the aftermath of these brief and intense moments; staring in the mirror or tossing in bed at night, where a realization that “something is not right” finds us in parasitical attachment, we commit to a new grand idea.

Our old understanding and conception of the universe, stacked and pieced together over the years, collapses like a Jenga tower. The futility of the game becomes obvious. Blind to ourselves — our faults, misinterpretations, and neglected responsibilities — we start to see the “utter failure” of life as it has been revealed to us. We see the truth of our parents, friends, society, and God.

There must be some reason for playing the game, for stacking the pieces.

Some may pathologize this feeling and call it a symptom of depression or anxiety. But it is much older, more instinctual, and haunting.

It is the feeling of alienation. A symptom of an irreconcilable disconnect between ourselves and the world. All the stories have been heard. All the hypocrisy has been revealed. The future is just another dull moment waiting to happen. In the words of Trent Reznor, “I believe I can see the future because I repeat the same routine.”

Naturally, this is an affliction of youth. It is the dark antithesis to the vitality of body and mind that expresses itself in the spirit of the heroic adventurer, who seeks not to willingly upend the fabric of the world, but it expand on it and gain wisdom in return.

This hanging cloud generally follows a time of relative economic prosperity and social cohesion. Look, for example, at the late 1960’s. Millions of young people sawed away the roots of their family expectations, traditions, and values and broke free into the world. Joan Didion witnessed the aftermath of this change. After spending a year living with and interviewing hippies in San Francisco during the “summer of love”, she wrote this:

“Adolescents drifted from city to torn city, sloughing off both the past and the future as snakes shed their skins, children were never taught and would never now learn the games that had held their society together. People were missing. Parents were missing. Those who were left behind filed desultory missing-persons reports, then moved on themselves.”

Less Than Zero

For the alienated and disconnected youth, the desire to transcend one’s cultural and personal limitations becomes a type of religious right. But there is a risk to this seeking. The risk of Toal spiritual and personal desensitization.

In the novel Less Than Zero, Bret Easton Ellis illustrates the black hole of decadence, nihilism, moral confusion, and lack of innocence that steps in the shadow of the path of the alienated youth.