Welcome to today’s edition of That's A Good Idea. If this is your first time reading, subscribe here.

One quick thing:

If there is a recent essay that has sparked your curiosity, given you a new idea, or in any way contributed positively to your daily life please consider supporting That’s A Good Idea with a $5 monthly subscription. I want, more than anything for TAGI to remain something you look forward to reading each week and your support helps me to gauge if I am on the right track. While I don’t write to make money, any small contribution is greatly appreciated. Additionally, if there is a specific topic, idea, or book you’ve read recently that you’d recommend me digging into, let me know in the comments below!

Why We Crave Horror

The fight-or-flight reaction is the most ancient biological response.

That instantaneous jolt; the grass parts on the savannah and the low murmur of a nearing beast is heard, a stranger cuts you off on the highway; the dark figure across the lamplit street crosses to your side. Why?

It existed before language and love. It existed before music and writing. It existed before the dawn of recorded history.

It’s a mechanism of self-preservation. It’s why you’re here.

Sometimes, away from the full-throttle terror of that millisecond moment, you think of the feeling. How would you have reacted if you knew what was about to happen? When do these moments emerge? Is there a pattern with people, places, and things where we find real danger?

You start to create a mental map of the world. You start to assign the terror of fight-or-flight to their appropriate places. And you consistently seek where those places might emerge, both consciously or subconsciously.

This is why we crave horror stories. We can simulate danger, feel fear, come to terms with it, and draw upon the symbols and themes in the world where fear embeds itself.

You can intellectualize this feeling. It’s what makes you different from the squirrel that runs up a tree when it sees a dog.

One of the places where we are most free is when we are scared. I think that when we are scared, there's a primal thing that happens to our minds, where we are liberated from some of the constraints of civilized society.

-Clive Barker, Author

Seeking to live in an extended state of fear is not a state of mind we typically crave. But it exists on the spectrum of human experiences just as love, grief, and joy do. We acknowledge the need to develop an awareness and consciousness toward these feelings. Yet we often sanitize or ignore what we fear — and where we find this feeling. We use horror as an excuse to speak to these fears, without the need to sit in hard conversation with our internal monologue or place ourselves in dangerous scenarios. That’s why the most terrifying stories; the ones that had us crawling into our parent’s beds as children, the ones that haunt us at work the next day, illustrate our fears at a level deep enough to confuse and pry beneath our assumptions of the world. They bring new and dormant fears out from behind the curtain.

One story, the story that all other horror is built on and influenced by, captured that range and depth of terror like no other.

Dracula by Bram Stoker.

Dracula: The Anatomy of Horror

"Dracula" is more than just the classic novel forced on you in your first year of English lit class; it's a roadmap for how to terrify at a bone-deep level. Dracula is to horror what Lord of the Rings is to fantasy.

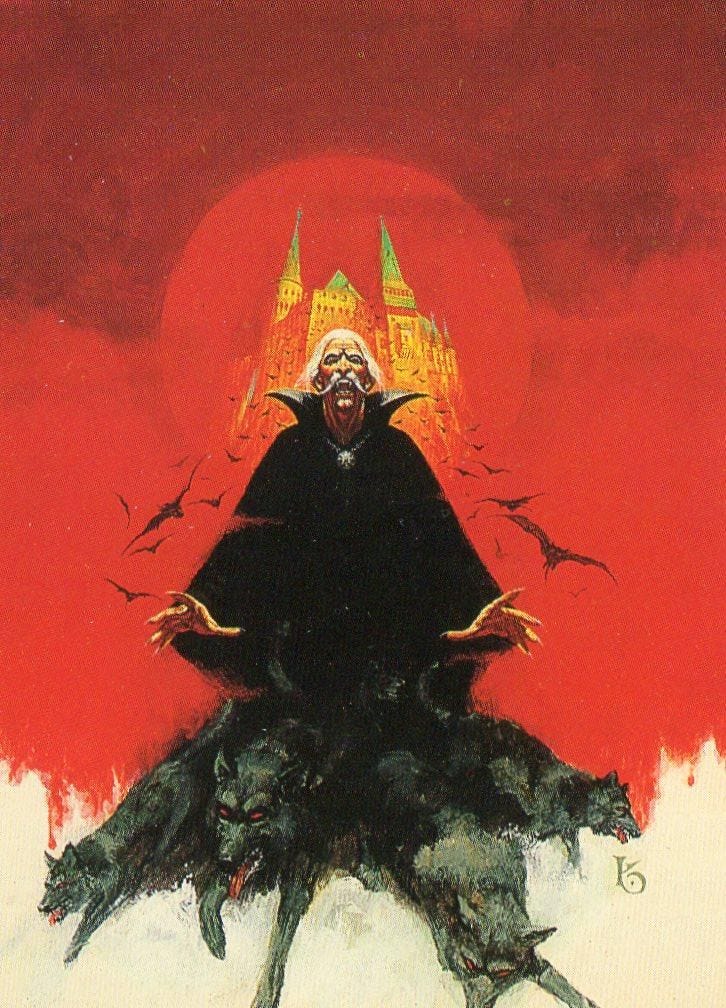

A sharp, sadistic, undead, and omnipresent old noble from the mysterious Transylvania region of Romania crosses the English Channel seeking new blood to feed his life force.

I won’t say much else, because if you haven’t read it, you need to.

The full depth of the Dracula story, why it’s been it has been reinterpreted, reimagined, and had empires built on top of it, is because of the lengths to which Stoker went to create a totalizing environment of fear.

“Dracula" is an epistolary narrative, told through the letters and diary entries of primary characters. This creates an immediate sense of history — of time and place. We’re not reading an omnipresent narrator babble on, we’re reading the first-hand accounts of those who were preyed upon and lured by the sadistic Count.

More than anything, Stoker understood that the fight-or-flight mechanism is only the punctuated response to immediate danger. Suspense and dread are what most of us regard as “fear”. It’s how we’re able to tolerate the punctuated heart-stopping jump scares. The more we linger on the balance beam of this feeling the more engaged with the material we become. Suspense, as Edgar Allen Poe had demonstrated in his works of Gothic fiction fifty years prior, must be set through our expectations; teased, and revealed, in the sub-text of the setting, characters, and general themes of the story. A well-crafted horror story reflects the dark world that exists outside of our general periphery. A world that we know exists, but seldom explore. The mysterious ghouls of society we glance at from afar, places that the lump in our throat tells us not to go near. We place ourselves in a fictional avatar when we come face-to-face with fear and suspense. We imagine briefly what lurks behind the door. Or we suppress these thoughts out of necessity, distract ourselves with a story of heroic transformation or love. Understanding the impulse to resist confronting fear, Stoker crafted “Dracula” to poke holes in the darkness. To addict us to fear without us knowing it.

It begins with the character of Count Dracula.

An embodiment of death, the fear of death, and the consuming desire of satanic darkness. He can shapeshift from a human form to that of a bat, wolf, and mist, his life force permeating normal reality with omnipresent evil. A soul black and empty and entwined with the living and breathing world that can only be sustained through human blood. In one aspect or another, Dracula exists in all the dark recesses of our minds.

The symbol of these ancient, and seldom explored thoughts, is Dracula’s infamous castle. Nestled in the wild and dark Carpathian Mountains, accessible by only a narrow road, perched atop a rocky outcropping on the edge of the mountain peering over the town; we’re aware of the symbolic gravity of the castle from the beginning. It is something ancient, broken, and evil — like the Count who calls it home.

We are in Transylvania, and Transylvania is not England. Our ways are not your ways, and there shall be to you many strange things. Nay, from what you have told me of your experiences already, you know something of what strange things there may be.

Count Dracula

Dracula is an agent of the unknown, descending on a world of order and strict codes of moral and social behavior, masking his addiction to innocent blood through a sharp tongue, a dignified voice, and a black-hole morality. This unknown, uncontrollable, haunting darkness is something Victoria England feared, and it’s what we fear now.

What makes Dracula so compelling, and so many other notable horror villains, is that violence is only the physical expression of a broad desire to control and corrupt the souls of man. The deeper undercurrent, the foundation that the act of physical violence is built on, is philosophy; or lack thereof. His moral code is predatory, mystical, contemptuous of humanity, and self-serving. A reflection of an immortal life.

I have a sort of empty feeling; nothing in the world seems of sufficient importance to be worth the doing.

Count Dracula

In the story, Dracula’s voyage from Transylvania to England can be seen as a symbol of the fear of foreign invasion prevalent in late 19th-century Europe. New ideas, a changing world, a diminishing of the traditional codes and norms of the day. What is worse than individual death? The slow and clawing death of an entire people, chewed upon by the un-dead embodiment of evil.

The horror that captivates us the most speaks to these fears. It’s what has made the vampire a cultural mainstay and it’s why we return to the horror genre again and again.

If we can sense the outer darkness; if we can experience it through the safety of the pages of a book or the comfort of a movie theater seat, we can approximate it and imagine its full incarnation without the need to subject ourselves to it.

We can develop a sense of where the fear response is located. These archetypes, personality traits, and acts of violence; a signal that something more malevolent and darker than the mortal world can fathom lay in wait around us. We don’t crave horror because we like being scared, we crave horror to preserve. To know the danger and develop a sixth sense for it so that it’s recognizable when it crosses our path.

As always, thanks for reading.

-Joe