Write & Lift is an ethos of personal and spiritual development through conscious physical exertion and practice of the writing craft. Through this effort to strengthen our bodies and minds, we become anti-fragile and self-respecting sovereign individuals. Through this effort, we may stand against untruth and evil and create a new culture of vitality, strength, and virtue.

Write & Lift Book Review: The Camp of the Saints

Yes, The Camp of the Saints is a real banned book. You’re not going to find it in your local bookstore. You’re not going to find it in any college literature curriculum. And you’d be lucky to find it available in re-print on Amazon. It’s tough to get your hands on. Luckily, I was able to find an excellent reading from Pete Quinones on his podcast feed (thanks Pete).

Today, Camp is branded as racist, xenophobic, and apocalyptic by our monitors of culture. Yet, in the decade after it was published in 1973, it was praised by President Ronald Reagan, Lionel Shriver, and William F. Buckley. It fell into online obscurity by the mid-2000s, but as the world that Camp imagines becomes an undeniable reality, it’s found a new audience; Viktor Orban, Marine Le Pen, and Steve Bannon have all cited its current importance. It’s an important book. Not because it’s “bad” but because it’s necessary to understand the rot at the heart of Western Civilization. Reading Camp in 2025 is like watching a car crash in slow motion, knowing the victims had fifty years of warning signs.

Raspail is honest in ways that all read-worthy fiction is. Disturbing in its prescience. Unflinching in its diagnosis. Honest about our blind spots. Similarly to how 1984 warned us about the dangers of totalitarianism, or Brave New World about the risks of a pleasure sick society, Camp brings to light the civilizational suicidality of toxic “empathy” and cultural decay. It’s primary thesis; in order to protect something you have to know what you’re protecting it from, is not a call to hate the “third world.” Rather, it’s an investigation into the strange worldview that many Western leaders today share. The idea that nations are a construct. That they are functionally the same regarding of ethnic heritage, religion, or cultural background. Nobody from Japan, or India, or Nigeria would permit a flood of migrants from halfway around the world to eat up resources, so why do we? It’s the question of the century, and a reflection of a worldview that all nations and peoples—besides ours—have preserved.

To understand Camp—and the author who wrote it—you have to understand the world as it was (for each recurring generation of humanity) and as it is now.

The Mirror We Refuse to Face

Published in 1973, Raspail’s novel depicts the arrival of a million Indian refugees on the shores of Southern France. One hundred ships carrying the world’s dispossessed, the starving, and the hopeless. The West, paralyzed by self-doubt and humanitarian platitudes, finds itself unable to turn away the armada. Decision-makers retreat into abstractions while the concrete reality bears down upon them.

No character in this novel escapes Raspail’s sword. The Western elites are soft, decadent, and pathologically self-hating. The migrants are portrayed not as noble sufferers but as a force of nature, an indifferent tide that will drown everything in its path (including themselves).

What makes the book disturbing is not just its unvarnished portrayal of different peoples and cultures, but its surgical dissection of how civilizations lose the will to survive. The Western characters don't succumb to outside conquest, they rationalize their own destruction as moral necessity.

As the “Armada” leaves the shores of India, news reaches French officials that they plan to arrive in the coastal Rivera. The boat will be at sea for months. They have time to plan, to think, to create contingencies. But they find no solution for the incoming crisis, the are racked with guilt; the horrors of past colonialism, the necessity for safehaven, the moral obligation of the French people to bear this sudden burden. Those who publically oppose the arrival of the incoming fleet are taken off air, or shunned from halls of power. Those who support it, are galvanized, using the migrant flotilla as a metaphor for their resentment and hatred of the percieved quasi-fascist French state.

In the opening scene (en-media-res) , an elderly Frenchman watches the ships near the coast from his villa window. He sets out the fine China, has a glass of cognac, and stares longingly at the centuries of stories within the walls of his home. He understands what is about to happen. As the city clears out, he grabs his gun and ventures out into the quiet streets where he encounters a young Communist. The boy, still a teenager, shouts at the old man to leave and the two of them start to argue. The boy says that he welcomes the migrants, that he can’t wait for the collapse and death of Capitalist society that has incubated him. The old man presses him on questions of culture, history, and religion; the boy scoffing and threatening him with each answer. Eventually, the old man, knowing that his home country is forever changed, shoots the boy and walks back home to enjoy the last moments with his estate. Such begins the story. The resigned death of the old world and the beating drums of the new one.

The most honest thing about Raspail’s vision is that he sees the fatal flaws in both worlds. The West dies not from external conquest but from internal rot; a crisis of meaning, a loss of belief in itself—the young boy from the first scene. The Third World masses in his novel aren't conquering heroes but desperate human beings following the path of least resistance toward survival. They take scraps of bread from children. They climb on the bodies of elders towards water or sun. Not because they are defective, but because this is what harsh Darwinian survival looks like to those who haven’t seen it.

Both sides are stripped of nobility in his telling. Both are revealed as human, driven by the most basic instincts: preservation, continuation, life at any cost.

The Prophecy

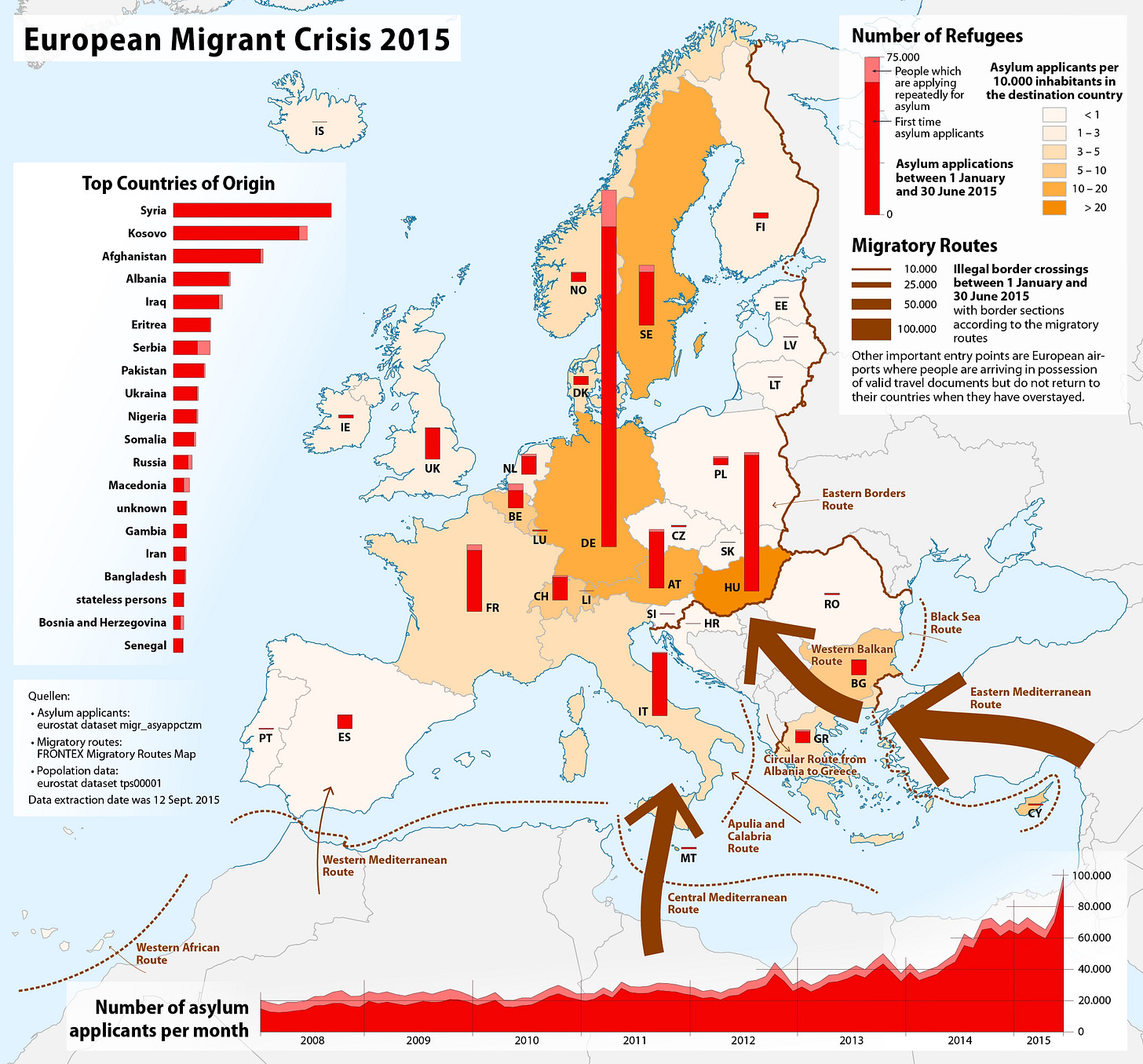

When Raspail penned this novel half a century ago, mass migration from the Global South to Western nations was a trickle compared to today. The Mediterranean wasn’t yet a graveyard of desperate souls trying to reach Europe. Western nations hadn't yet seen the fundamental demographic transformations that now shape their politics and culture.

What Raspail foresaw was not just migration itself, but the moral paralysis of Western elites when faced with it. The novel depicts journalists, politicians, and intellectuals who cannot bring themselves to defend their civilization because they no longer believe it deserves defense. Sound familiar?

Today’s European politics—from Brexit to the rise of nationalist parties across the continent—are unintelligible without understanding the underlying anxieties Raspail identified. The novel has become required reading not because of its literary merits, but because of its diagnostic power.

Raspail’s writing is, at times, deliberately provocative, designed to offend modern sensibilities. The writing can be heavy-handed. The characterizations of non-Western peoples often cross into caricature. Its political incorrectness is not incidental but essential to its project. Progressive readers will find its language and characterizations of the Third World repellent. Conservative readers will recognize their fears rendered in grotesque, undeniable forms.

But both miss a deeper point. Raspail isn’t writing about immigration policy. He's writing about civilizational confidence, about psychological collapse that precedes physical defeat.

Why It Matters Now

The value of reading Camp today is not found in its proposed solutions, which are largely nonexistent. It’s found in its willingness to stare unflinchingly at questions most of us prefer to avoid.

What are the limits of humanitarian obligation?

What happens when cultures with fundamentally different values must share the same space?

Can universalist principles survive contact with tribal realities?

What does a civilization owe to itself and its future generations?

We no longer allow these conversations in mainstream discourse. Even raising such questions gets one relegated to the fringes. The establishment left frames all discussion of migration limits as bigotry. The establishment right pays lip service to borders while embracing the economic benefits of cheap labor.

Meanwhile, ordinary citizens across the Western world increasingly feel that something essential is being lost, that the pace of change has accelerated beyond their consent.

Camp is valuable precisely because it speaks to this unease in ways that sanitized political discourse cannot. It gives voice to fears that, when suppressed rather than addressed, fester and emerge in uglier forms.

As always, thanks for reading

-Joe

‘These are the ones who hold open the gates for the barbarians. The barbarians never take a city till someone holds gates open for them…resist it while you can.’ -Christopher Hitchens

There's a Russian nuisance streamer who is currently being detained in the Philippines for harassing the local citizens in Manila. All over the country, and all around the world, Filipinos were shouting with chests puffed up on how no foreigner should ever think about harassing, exploiting, and mocking their country. Despite knowing how shitty it is, Filipinos still love their country enough to defend her from foreign harassment. I say that to say - I wish I saw that same kind of energy in the West, particularly in the US and the UK. Americans deal with far worse threats than nuisance streamers, yet are so paralyzed by the public stigma around perceived bigotry, or the social status you get for being an "ally", that they'll watch their country crumble just so they can be perceived as "compassionate", or that they helped destroy the "imperial, colonialist, racist, sexist" monolith that is the West. Truly sad.